When Heritage Becomes a Hustle: The Controversial Legacy of Tom Aicklen and the Rise of Fabricated Tribes

- Ishmael Bey

- May 31, 2025

- 10 min read

Updated: Jun 2, 2025

“ It’s all about the Greeeeeen ” - Tom Aicklen to Chief Warhorse when asked about the motivation of him assisting fraudulent Native American Tribes in Louisiana

In a time when the reclaiming of Indigenous identity is more crucial than ever, few figures are as divisive in the Southeast United States as Tom Aicklen. Known as a local historian and heritage promoter from Lacombe, Louisiana, Aicklen has long positioned himself as a cultural advocate—particularly for the so-called Bayou LaCombe Choctaw. But deeper scrutiny reveals a pattern that raises critical questions about cultural appropriation, identity fabrication, and the exploitation of Indigenous history. Until there was somebody brave and bold enough to have a direct and honest conversation with Tom in public he would have remained being the bloody mouthed Wolf in Sheep's clothing until he was exposed as the fraud he is by Chief Warhorse. The public owes a debt of gratitude for such an act.

Despite his contributions, Aicklen has faced criticism regarding his role in promoting certain Native American identities. Some sources allege that he was involved in creating or promoting groups like the Bayou LaCombe Choctaw, Jena Band of Choctaw in Louisiana, and MOWA Choctaw, which have been accused of appropriating Native American heritage for personal or financial gain.

The Making of a “Tribe”

Aicklen’s early work in Lacombe centered on preserving rural and Creole history. As Heritage Chairman for the Bayou Lacombe Bicentennial Community project in 1975, he helped establish the Bayou Lacombe Rural Museum. On the surface, these efforts appeared admirable. Yet, behind the curated museum dioramas and oral histories lies a more troubling agenda: the promotion of self-identified “tribal” groups that lack historic or genealogical continuity with established Native nations.

The Bayou LaCombe Choctaw—often cited in relation to Aicklen—has never been federally or state-recognized, nor have they been able to provide the rigorous documentation required to prove continuous tribal existence. Critics argue that the group was fabricated, or at least heavily embellished, to tap into the cultural cachet (and in some cases, funding) associated with Native identity.

Bayou Lacombe Choctaw

Real Harm to Real Tribes

Why does this matter? Because the invention of tribal identity isn’t just a harmless form of cultural pride—it’s a direct assault on the sovereignty and recognition of real Indigenous nations.

Federally recognized tribes must meet strict criteria, including continuous community existence, political influence over their members, and direct descent from a historical tribe. When groups like the Bayou LaCombe Choctaw attempt to bypass these requirements with incomplete or misleading genealogical claims, they dilute the legitimacy of Native status. Worse, they compete for limited grants, resources, and legal protections that are already scarce for real Indigenous communities.

In particular, Aicklen has been linked by critics to other dubious groups such as the MOWA Band of Choctaw and the Jena Band of Choctaw—entities that have drawn skepticism from federally recognized Choctaw leadership and academic scholars alike.

"Confessions of the Pale Imposter"

A recent exposé titled “Confessions of the Pale Imposter” underscores how this dynamic plays out. In it, documents and communications attributed to Aicklen detail internal disputes about power, profit, and public recognition within these “tribes.” Whether or not every claim can be verified, the very existence of such a dialogue suggests a level of artifice and opportunism that stands in stark contrast to the lived experiences of Native peoples.

Cultural Theft in Plain Sight

This isn’t just a story of one man’s ambition. It’s part of a broader trend of non-Native individuals and communities attempting to retroactively construct Native identity—often based on vague ancestral myths, DNA tests, or unverified family lore.

These actions amount to cultural theft. They erase the very real suffering, resilience, and survival of Indigenous people. And when these “tribes” host public powwows, offer spiritual ceremonies, or engage with local governments, they muddy the waters for policymakers, educators, and the public. The Path Forward: Accountability and Respect

We must hold individuals and groups accountable when they distort history for personal or financial gain. This means demanding transparency from cultural institutions, verifying genealogical claims, and listening first and foremost to recognized tribal governments and Native community leaders.

Tom Aicklen may see himself as a custodian of Louisiana heritage, but history must not be rewritten to serve ego or ambition. Indigenous people are not footnotes in someone else’s story—they are the authors of their own.

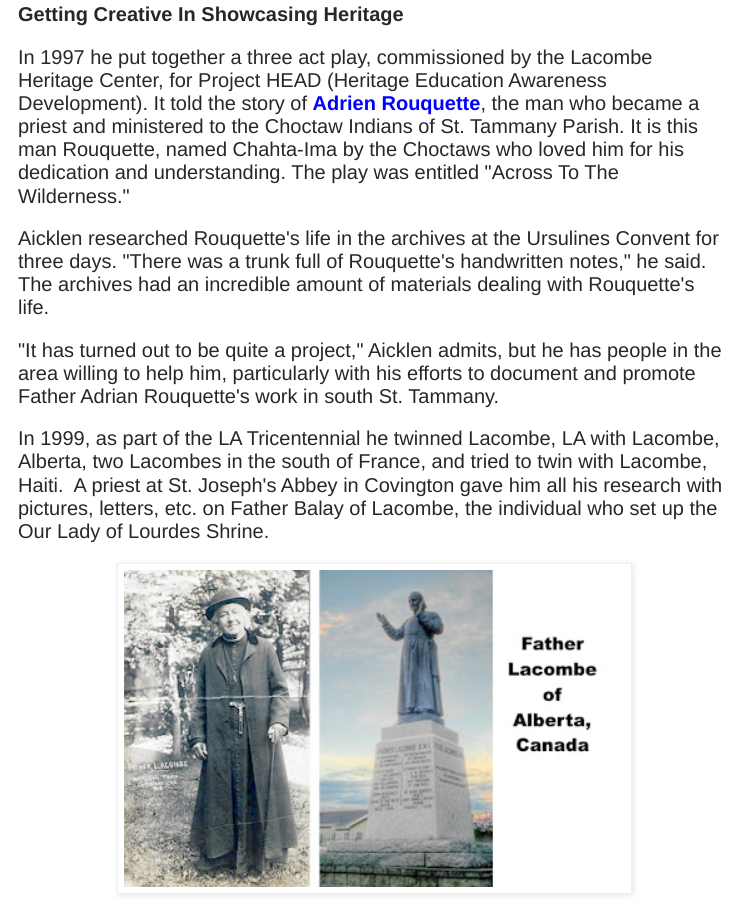

In Tom's own words : CHOCTAW RENAISSANCE

A draft prospectus by Tom Aicklen

March 8, 2011

The story of the Chacta (Choctaw) begins in the creation myths of the Maya of Central America. Evidential research done by the Chacta Studies Program of the Lacombe Heritage Center indicates that about 1,300 years ago the followers of the Mayan rain god Cha’ak migrated out of a dry and desiccated Yucatan northward through Mexico and eastward into Louisiana, eventually spreading up the Mississippi River valley and across the Gulf South to become the culture known as the Temple Mound Builders. Legends of the Choctaw, and other indigenous people of the Southeastern United States, tell of this migration of the Chacta, the followers of Cha'ak, led by the sacred Red Pole of the Chacta.

In a partnership between the Lacombe Heritage Center and St. Tammany Parish, this exciting story, which chronicles the legends and facts of the Choctaw experience, is to be presented by the Theater in Education company of the Lacombe Heritage Center in the form of an outdoor drama entitled, “Across to the Wilderness.”

A performance facility, CHACTA: Choctaw Heritage Awareness Commemorative Theater Area at the Camp Salmen Nature Park in Slidell is one site for this business enterprise. (The other site is the Francois Cousin Bayou Heritage Park on Bayou Lacombe.) This edutainment venue is an important community enhancement and cultural economic development project that will enrich our local heritage, entice tourists to our area, and provide employment for youth.

The Theater in Education program is designed to serve not only academic purposes, but also assist language revitalization in a joint planning partnership with the St. Tammany Parish School Board and our Northshore Technical Community College , and other appropriate organizations and individuals. This reciprocal relationship encourages mutually beneficial results that will seed ongoing initiatives. These will be key developments in cultural preservation and work with the nonprofit Lacombe Heritage Center and other organizations to improve the quality of life in the region. It is designed to serve the cultural economy as a permanent exhibition of indigenous art, history and culture in the creative and performing arts, to inspire other imaginative initiatives, and to revitalize the region’s previously neglected heritage resources.

The Theater in Education curriculum will create and perform quality theatrical productions that are also educationally relevant. This program of study promotes diversity and helps explore cultural understanding that offers citizens and tourists an opportunity to learn about an American civilization to which we are all connected. It provides art-based learning strategies that create many possibilities for collaborative learning and teaching designs.

Our goal is to create programs which will serve as a model for both artistic excellence and significant learning that engages younger people in the community and creates opportunities for participants to experience literature, theater, art, music and dance that weaves cultural and environmental literacy and service in a matrix of creative talent and learning.

In developing these programs we have made contacts with the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, the MOWA Band of Choctaw in Alabama, the Mississippi Band of Choctaws, and the Jena Band of Choctaw Indians in Louisiana. We plan on cooperation with them as associates in the Choctaw Renaissance.

Tom Aicklen’s Creation Story of the Choctaw That he feeds to the masses

Local history buff Tom Aicklen is developing the hypothesis that a group of Maya, known as the Chacta, translated as “followers of the rain God Cha’ak,” left their Central American homeland after centuries of drought, and migrated for forty-two years through Mexico and along the Gulf coast. During their journey they would make periodic stops to raise crops.

“At each place they settled, you can trace the ritual of the lighting of the fires for the Feast of the Dead,” explained Aicklen noting that he believes the Maya brought their ritual to Lacombe, but performed it in May. “They would build bonfires in the woods to attract their descendants. They felt the stars were their descendants and by lighting the fires it would draw the spirit back to earth and they could commune with them.”

Aicklen believes that it was these Chacta natives who came to be known as the Choctaw, and that from their Pagan-style celebration evolved the Christian ceremony still observed in area cemeteries to this day. Pine torches were used for light and participants decorated the graves of their ancestors with evergreen boughs of juniper and cedar to create the form of an encircled cross, a Native American symbol for life and continuation.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Father Adrien Rouquette, a Louisiana Creole whose mother was part Choctaw, grew up among the tribe as a child, later becoming a missionary to the Lacombe Choctaw with hopes of introducing them to Catholicism. Rouquette had a deep devotion to nature and revered the Choctaw way of life. He grew his hair long, ate their foods, and eventually was invited to the Feast of the Dead.

Is there a connection between ancient Mayans and those who live in Lacombe today and annually observe a particularly beautiful and deeply-rooted All Saints Day tradition? The answer may well be lost in the mists of time.

What is clear is that today, 150 years later, this vibrant tradition continues carried on by Creole families descended from early Native American, African American, and French settlers.

"I have told but a very few people of my association with Walt Disney Studios and the American Broadcasting Company in Hollywood," he said, but he has dozens of anecdotes and the photos to go along with them tell of his Disney connection.

Bonus Article

The story begins on a fateful day, November 22, 1963, when Disney arrived in New Orleans, unaware that it was the same day President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. “ The aftermath of the assassination and the ensuing weekend marked a turning point. Rester recounted how Walt Disney suddenly decided to pack up and return to California. The reason for this abrupt change was, quite astonishingly, a compliment to Caruso: he was the first Louisiana public official who had spent extended time with Rester without ever asking for a bribe.

While this account does not imply that all Louisiana politicians were corrupt, it is a glimpse into the intricate world of politics and deals. This 'what-if' story leaves us to ponder the fascinating possibility of having a Disney World in Louisiana. What could have been remains a question mark, as Disney ultimately chose Florida as the home for his iconic Walt Disney World Resort, which opened its doors on October 1, 1971.

The city of New Orleans had always been an inspiration for Disney, as demonstrated by the addition of New Orleans Square at Disneyland in 1966. Mayor Caruso reflects on the missed opportunity and envisions how it might have reshaped the city and state. Disney World in Louisiana could have been a game-changer, combining the unique charm of the city with the magic of Disney."

https://1079ishot.com/was-disney-world-really-almost-built-in-louisiana/

The Dangers of Fraudulent Misinformation in American Indian History

The consequences of fabricating American Indian identity go far beyond cultural confusion or misrepresentation—they result in real harm to Indigenous communities. When the motivation is profit or personal ego, the erosion of historical truth becomes a form of violence, undermining decades of work by Indigenous scholars, tribal elders, and activists who fight for recognition, sovereignty, and survival. 1. Undermining Tribal Sovereignty and Federal Recognition

Federally recognized tribes are sovereign nations with unique political, legal, and economic rights. These rights are not arbitrarily assigned—they are earned through generations of struggle and meticulously documented genealogies and histories. When false groups claim Indigenous status without meeting federal criteria, they jeopardize these hard-won gains.

As scholar Circe Sturm notes in her book Becoming Indian: The Struggle over Cherokee Identity in the Twenty-First Century (Princeton University Press, 2010), the rise of “racial shifting” and self-identification based on tenuous or invented links to Indigeneity complicates efforts for real tribes to assert legal authority and protect their resources.

“The proliferation of groups claiming Indian identity without cultural, political, or genealogical ties to tribal communities threatens to devalue legitimate tribal citizenship” — Sturm, 2010

2. Exploiting Cultural Capital for Financial Gain

Events like powwows, land grants, heritage festivals, and tribal business designations (e.g., 8(a) contracting with the SBA) can become lucrative for groups claiming Native status. Fraudulent actors often capitalize on this by setting up non-profits or for-profit ventures under the guise of tribal affiliations, all while diverting funds that were intended to empower disadvantaged Native populations.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) has reported that fraud and abuse in minority contracting programs often involve misrepresentation of Native identity. In a 2011 report, the GAO warned that “contracting fraud schemes undermine the ability of programs to serve disadvantaged businesses as intended.” (GAO-11-440T)

3. Erasing Real Histories and Oral Traditions

When individuals invent tribes or falsely claim Native lineage, they often rewrite tribal histories to suit their own narratives—usually omitting colonization, genocide, or forced removals. This revisionism distorts the public’s understanding of Indigenous resistance, ceremony, and survival, replacing it with sanitized or romanticized myths.

Dr. Kim TallBear (Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate), author of Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science, warns that fraudulent claims also blur the lines between cultural heritage and genetic essentialism.

“Identity cannot be distilled from a blood test, nor should it be determined by individuals who are not embedded in the community.” — TallBear, 2013

4. Harming Youth and Education

False history impacts education by introducing misinformation into classrooms, museums, and curricula. Children—Native and non-Native alike—grow up with distorted narratives that omit the lived realities of Indigenous people. Fraudulent “tribes” sometimes offer cultural education programs or give presentations in schools, spreading inaccuracies that are difficult to correct once institutionalized.

These miseducations contribute to broader ignorance about treaty rights, land claims, and historical trauma, reducing Native people to folklore or costume rather than living political entities.

5. Ego Over Ethics: When “Playing Indian” Becomes a Lifestyle

The allure of Indigenous identity is potent for some—particularly those seeking a sense of belonging, prestige, or uniqueness. Scholar Philip J. Deloria explores this in Playing Indian (Yale University Press, 1998), where he documents how non-Native Americans have historically romanticized and impersonated Native identity to satisfy personal or ideological desires.

“From Boston Tea Party revolutionaries to hobbyist powwow participants, playing Indian has offered non-Indians a way to assert American-ness while erasing the people they imitate.” — Deloria, 1998

In modern cases, this performance is often magnified by social media, grants, or public recognition. Fraudulent leaders position themselves as cultural gatekeepers—while ignoring actual tribal leadership and protocols.

Protecting the Integrity of Indigenous Identity

Indigenous identity is not a costume, a grant application, or a spiritual brand—it is a legacy, carried by communities who have survived centuries of dispossession, boarding schools, and broken treaties. When individuals like Tom Aicklen—or any self-appointed “chief”—construct a tribal identity for financial or egotistical reasons, they are not just lying to the public. They are robbing Indigenous peoples of the dignity, voice, and power they continue to fight for.

The solution is not just to call out the fraud—it is to elevate real Native voices, support tribal sovereignty, and educate the public on how to discern authentic Indigenous presence from opportunistic imposture.

FIRST TRIBE

Comments