The Science of Supremacy Eugenics and America's War on Non-White Lineage

- Ishmael Bey

- May 24, 2025

- 10 min read

By Ishmael Bey

John Powell (1882–1963): Composer, White Supremacist, and the Dark Side of American Musical Heritage

John Powell is a name that may resonate with classical music enthusiasts for his contributions to early 20th-century American piano and folk music. But behind his talents as a composer and pianist lies a deeply disturbing history. Powell was not only a musician; he was also a vocal proponent of white supremacy and racial segregation. His racist ideologies shaped not only his personal beliefs and music but also influenced laws and attitudes in Virginia and beyond. Early Life and Musical Accomplishments

Born in Richmond, Virginia, on September 6, 1882, John Powell was a child prodigy who quickly excelled in academics and music. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa from the University of Virginia and later studied in Vienna, where he trained under renowned instructors like Theodor Leschetizky (piano) and Karel Navrátil (composition) (Song of America).

He launched a successful international concert career and composed several major works, including orchestral rhapsodies and piano concertos. Powell also dedicated a portion of his career to studying and preserving Appalachian folk music, co-founding the White Top Folk Festival in 1931.

But his ethnomusicological interests were far from inclusive. He believed that the only true American music was rooted in Anglo-Saxon traditions, dismissing both African American and American Indian contributions as inferior or corrupting influences.

Powell’s Racist Ideology: The “Anglo-Saxon” Obsession

Powell’s worldview was underpinned by the belief that Anglo-Saxon heritage represented the pinnacle of civilization. He viewed cultural purity as vital to national identity and saw other racial or ethnic influences as threats to societal cohesion. This belief wasn’t just a private conviction; it became a public crusade.

🏛️ Co-founder of the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America

In 1922, Powell co-founded the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America with fellow white supremacists Dr. Walter Plecker (Virginia’s registrar of vital statistics) and Earnest Sevier Cox, a racial separatist and proponent of "repatriating" Black Americans to Africa (Wikipedia).

The Club’s slogan—“America for the Anglo-Saxon”—reflected Powell’s belief that all non-Anglo peoples, including Black, American Indian, and immigrant populations, were racially and culturally inferior. The club’s political efforts led directly to one of the most infamous laws in Virginia’s history. The Racial Integrity Act of 1924

Through the lobbying power of the Anglo-Saxon Clubs and Powell's own persuasive writing and speeches, the Racial Integrity Act of 1924 was passed in Virginia. The law implemented the "one-drop rule," classifying anyone with even a single drop of non-white blood as non-white. It banned interracial marriage and forced all residents to register their racial identity, effectively erasing Native American identity in Virginia by folding Indigenous ancestry into the “colored” category.

According to historian Ariela J. Gross, this legal move was part of Powell and Plecker’s coordinated effort to preserve what they called “racial purity” ([Gross, What Blood Won’t Tell, 2008]).

🪶 Powell’s Views on American Indians

Powell’s racist framework extended to American Indians, whom he viewed through the same eugenicist lens that he applied to Black Americans. In a speech and essay titled "The Breach in the Dike", Powell argued that intermarriage between whites and Indigenous Americans threatened to “dilute” the racial strength of the Anglo-Saxon stock.

He opposed the recognition of American Indian tribes in Virginia and supported policies that would reclassify them as "colored"—a devastating move that effectively stripped many tribes of their legal and cultural identity. This reclassification was enforced aggressively by Walter Plecker, often using Powell’s writings as justification.

The Native American advocacy group Racial Integrity and the Virginia Tribes has condemned Powell for his role in what they describe as “paper genocide”—the erasure of Native American identity through bureaucratic means (University of Virginia Library Exhibit).

Music as Propaganda: Rhapsodie Nègre and Beyond

One of Powell's most notorious musical works is "Rhapsodie Nègre", published under the pseudonym Richard Brockwell. In this piece, Powell portrayed African music in a deliberately primitive, mocking tone. He described Black people as “savages” and “children among the races,” framing the composition as a caricature of Black musical traditions rather than a celebration.

This was no innocent cultural experimentation. It was a musical expression of Powell’s white supremacist ideology—a sonic argument for the inferiority of non-Anglo cultures.

Legacy and Reassessment

Despite his accomplishments in music, Powell’s racist ideologies have caused institutions to reassess their relationship with his legacy.

In 2010, Radford University removed his name from a building after students and faculty brought attention to his role in white supremacist politics. His legacy today is a complicated one: a talented composer and pianist whose work cannot be ethically separated from his destructive and exclusionary beliefs.

Sources

Song of America – John Powell

University of Virginia Library Exhibit on John Powell

Ariela J. Gross, What Blood Won’t Tell: A History of Race on Trial in America (Harvard University Press, 2008)

Gregory D. Smithers, The Virginia Indian Heritage Trail (2007)

Kevin C. Murphy, Legacies of Racial Intolerance in Virginia (2011)

🧬 A Dangerous Alliance: John Powell and Walter Plecker

To fully understand the destructive legacy of John Powell, one must examine his close and deliberate alliance with Dr. Walter Ashby Plecker (1861–1947)—the first registrar of Virginia’s Bureau of Vital Statistics and a fellow architect of scientific racism in the American South.

🧠 The Eugenics Movement Connection

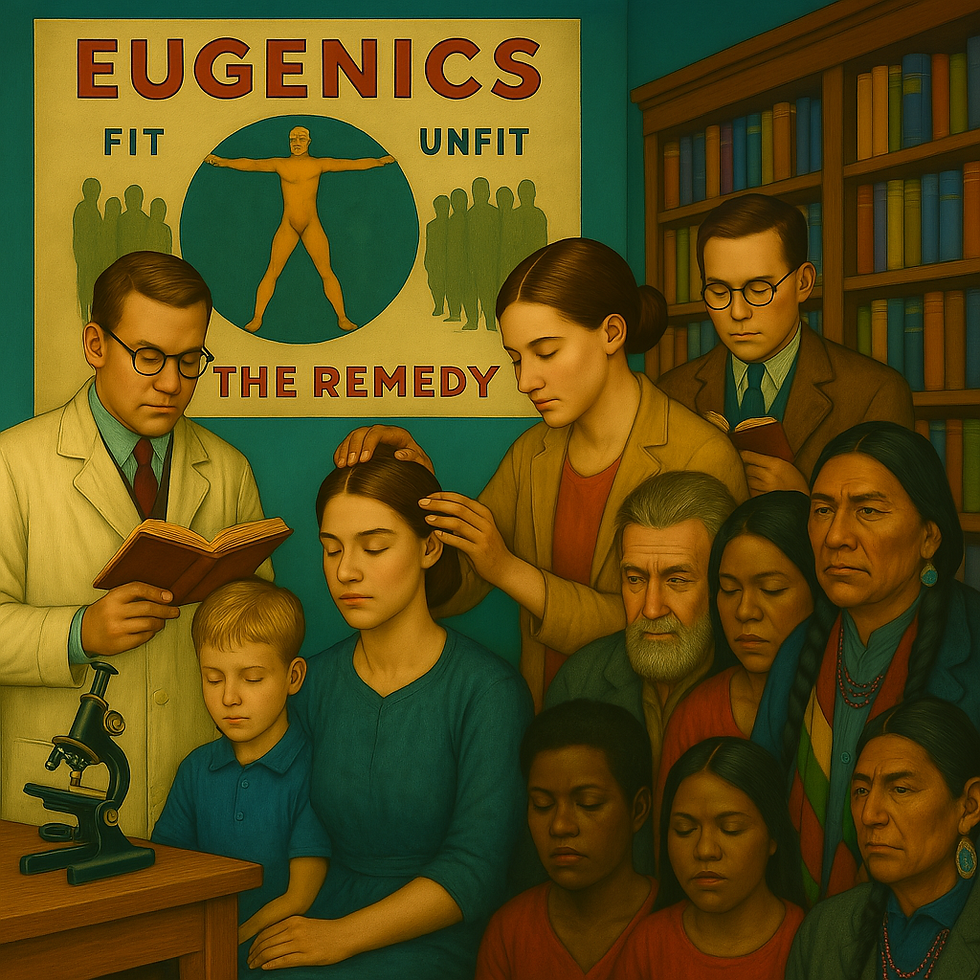

Both Powell and Plecker were deeply influenced by the early 20th-century eugenics movement, which promoted the idea that selective breeding could "improve" the human race. Eugenicists believed in preserving the "purity" of white, especially Anglo-Saxon, bloodlines while preventing what they considered the degradation of the gene pool by nonwhite or “mixed” populations.

Powell and Plecker found common cause in their fear of racial “amalgamation.” Powell provided the ideological and cultural narrative—arguing that American identity must be rooted in white, Anglo-Saxon heritage—while Plecker carried out the bureaucratic enforcement of these ideas, wielding his office like a weapon of racial control.

Virginia laws approved in 1924, known as the Racial Integrity Act, sought to advance white racial purity in part by banning interracial marriage.

Crafting the Racial Integrity Act of 1924

Their most notorious collaboration was the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which was largely drafted and promoted by Powell and Plecker through the vehicle of the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America. Powell was the organization’s most eloquent spokesperson, often writing pamphlets, giving speeches, and using his public profile as a composer to lend legitimacy to the club’s racial agenda.

Plecker, meanwhile, used his government position to institutionalize Powell’s vision. He maintained meticulous records of births, marriages, and deaths, ensuring that individuals with even traceable Native American ancestry were reclassified as “colored.” This effectively erased the legal and cultural identities of multiple Virginia tribes, such as the Monacan and Chickahominy.

In a letter archived at the Library of Virginia, Plecker praised Powell as a “man of vision and courage,” referring to him as a brother-in-arms in the campaign to “save the white race from mongrelization.”

🧾 The Paper Genocide of Virginia Indians

Powell and Plecker's policies did more than stigmatize; they led to what many Indigenous advocates call “paper genocide”—the systematic erasure of Native American identity through legal documents.

For instance, children born to American Indian parents in Virginia were often recorded as "Negro" or "colored" by the state registrar’s office. Even tribal members with documentation and ancestry going back centuries were denied their racial classification, invalidating their claims to land, federal recognition, and tribal belonging.

This institutional erasure was a direct result of the Powell-Plecker campaign. Powell’s anti-Native writings and folk ideology were cited in Plecker’s communications and training materials to justify these reclassifications.

Cultural Propaganda and Pseudoscience

Powell used his platform not just in legal lobbying but also in cultural spheres. He published essays like “Music and the Nation,” where he claimed that only Anglo-Saxon folk music represented the “soul” of American civilization, dismissing all other traditions—including Indian and African American—as degenerate.

Meanwhile, Plecker published state-sponsored “circulars” attacking mixed-race communities such as the Melungeons and the Rappahannock people, calling them “mongrels” and frauds who threatened white purity.

Together, Powell and Plecker represented a full-spectrum assault: from music to medicine, from the concert hall to the courthouse.

Long-Term Impact

The Powell-Plecker alliance has had multi-generational consequences. The Racial Integrity Act remained on the books until 1967, when it was overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court in Loving v. Virginia. But the bureaucratic and cultural damages persist.

Many Virginia Indigenous tribes only regained state or federal recognition in the 21st century, decades after Powell and Plecker's efforts to erase them.

The eugenics movement in the United States—particularly in the early 20th century—was used to systematically misclassify American Indians through coordinated efforts involving government policy, medical authorities, vital records offices, and mass media. This campaign was especially pronounced in states like Virginia, where white supremacist ideologues like Walter Plecker and John Powell worked hand-in-hand to enforce a vision of "racial purity" that excluded Indigenous people from legal and cultural recognition.

Here’s a detailed look at how the eugenics movement enabled this misclassification:

Eugenics Ideology: White Purity as a National Imperative

Eugenics held that society could be improved by controlling who was allowed to reproduce, based on the belief that some races and ethnicities were biologically superior. In this hierarchy, Anglo-Saxons were seen as the ideal—intelligent, moral, and civilized—while non-white populations were described as “degenerate,” “feeble-minded,” or “primitive.”

This racial pseudoscience positioned American Indians, like Black Americans, as a threat to white racial purity, particularly in cases of interracial mixing. Government Machinery: Vital Records and the “One-Drop Rule”

🔹 The Racial Integrity Act of 1924 (Virginia)

Spearheaded by Walter Plecker, this law institutionalized a binary racial classification system: everyone in Virginia was either "white" or "colored." There was no legal room for American Indian identity. Plecker believed that most individuals who claimed Indigenous heritage were actually of mixed Black ancestry and used this law to classify them as "Negro" or "colored"—regardless of community identity, cultural practice, or genealogical record.

❝ "There are only two races in Virginia. The white race and the colored race." —Walter Plecker

Vital statistics officers were instructed to reject birth, marriage, and death records that listed “Indian” as a racial category unless the family had documented proof predating 1850—an impossible standard for most tribal descendants due to slavery, displacement, and the destruction of earlier records.

This practice effectively erased American Indian identity on paper, a process often referred to as “paper genocide.”

Bureaucratic Enforcement: State Agencies and Schools

Plecker sent threatening letters to hospitals, schools, and midwives warning them not to register births with “Indian” as a race. He kept files on families he believed were falsely claiming Aboriginal ancestry, and even cross-checked church records and census data to reclassify entire family lines as “colored.”

This meant that:

Native children were often forced to attend segregated Black schools.

Tribes could not access federal services or land allotments intended for Native peoples.

Interracial marriages involving Indigenous people were criminalized under misclassification laws.

In many cases, Indigenous families fled the state or hid their identity to avoid persecution.

Media Support: Propaganda and Public Opinion

The media played a key role in reinforcing eugenicist ideas and justifying the erasure of American Indian identity:

Newspapers published articles warning about "mongrel races" diluting the white population.

Eugenicists were featured as credible scientists and quoted in editorials, framing Native identity as a fraud.

Popular science magazines described the rise of mixed-race groups like the Melungeons, Lumbee, and Rappahannock as a “problem” that needed to be managed.

John Powell, for example, used essays and public speeches to argue that “authentic” American culture was rooted only in white Anglo-Saxon traditions. He denied the legitimacy of African American and Indigenous music, promoting the idea that these cultures had no place in American identity.

Tribal Recognition Delayed by Decades

Because of these government-driven racial reclassifications:

Virginia tribes lost their legal identity and were not recognized by the state or federal government for most of the 20th century.

The Monacan Indian Nation, for example, was not granted federal recognition until 2018.

Tribal land claims and cultural heritage protections were systematically denied.

The erasure also disrupted genealogical continuity, making it difficult for descendants to prove tribal affiliation when recognition efforts resumed in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Sources & Further Reading

Ariela J. Gross, What Blood Won’t Tell: A History of Race on Trial in America (Harvard University Press, 2008)

Helen Rountree, Pocahontas’s People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia Through Four Centuries

Library of Virginia - Racial Integrity Act

“John Powell and White Supremacy” – University of Virginia Exhibit

National Museum of the American Indian – “Erased by the Pen: The Paper Genocide of American Indians”

Virginia Indian Heritage Trail (2007)

Key States with Similar Laws to Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act

🔸 North Carolina

Maintained strict one-drop rules and racial classification policies.

Had state eugenics boards that sterilized thousands, disproportionately affecting people of color, the poor, and those labeled "feebleminded."

Also denied Indigenous identity for certain groups, such as the Lumbee, who were often classified as "colored."

🔸 South Carolina

Prohibited interracial marriage and enforced racial classification.

While it didn’t have a “Racial Integrity Act” by name, its legal and social practices followed the one-drop rule in practice.

🔸 Tennessee

Banned interracial marriage and used racial classification in vital statistics.

Also conducted forced sterilizations under its eugenics program.

🔸 Georgia

Enforced strict anti-miscegenation laws.

Followed the one-drop rule in state documents and census reporting.

Indigenous people were often lumped into the “colored” category, particularly if they had mixed ancestry.

🔸 Alabama

One of the last states to repeal anti-miscegenation laws (not until 2000 via referendum).

Used the one-drop rule and supported eugenics-based sterilization programs.

🔸 Mississippi

Maintained similar racial classification systems based on color lines.

Enforced legal distinctions between white and nonwhite, impacting American Indian groups like the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians.

🔸 Kentucky

Enacted racial purity laws and used racial classification in vital records.

Implemented eugenic sterilization laws under the guise of public health.

🔸 Maryland

Passed anti-miscegenation laws in the 17th century and upheld racial classification practices well into the 20th century.

Used legal definitions of race to restrict land ownership and civil rights.

🏛️ 30+ States with Eugenics Laws

By the 1930s, over 30 states had eugenics-based sterilization laws. These were often paired with:

Racial classification in birth and marriage records

Anti-miscegenation laws

Racial exclusion in education and housing

These systems created legal definitions of race that mirrored the logic of Virginia's Racial Integrity Act, even if they didn't carry the same name.

📜 The “One-Drop Rule”

Virginia’s formal codification of the one-drop rule in 1924 influenced national thinking. Many other states used this unwritten rule in schools, courts, and public policy to determine racial status, especially in cases involving Indigenous or mixed-race identity.

📚 States That Later Overturned These Laws

The landmark Loving v. Virginia (1967) case struck down Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act and all remaining anti-miscegenation laws nationwide. At the time:

16 states still banned interracial marriage, including AL, AR, FL, GA, LA, MS, NC, SC, TN, TX, and VA.

Many states also began reviewing their racial classification systems following the ruling.

🧾 Summary Table

State | Anti-Miscegenation Law | Eugenic Sterilization | One-Drop Rule | Misclassified Indians |

Virginia | Yes (Racial Integrity Act) | Yes | Codified | Yes (Monacan, others) |

North Carolina | Yes | Yes | Yes (practice) | Yes (Lumbee, others) |

South Carolina | Yes | Yes | Yes (practice) | Yes |

Georgia | Yes | Yes | Yes (practice) | Yes |

Alabama | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Mississippi | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Tennessee | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Kentucky | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Maryland | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

“The Racial Integrity Act of 1924,” Library of Virginia https://www.lva.virginia.gov/

Alexandra Minna Stern, Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America (University of California Press)

Ariela J. Gross, What Blood Won’t Tell (Harvard University Press)

PBS: Eugenics and America https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/eugenics-movement/

North Carolina Justice for Sterilization Victims Foundation

FIRST TRIBE

Comments